An in depth look at treatments for overactive bladder

Autore:We have previously discussed the presentation and incidents of overactive bladder (OAB). In this second article, consultant urologist, Mr Ranjan Thilagarajah outlines the treatment options available for this common condition. Here we take an indepth look at the treatment for OAB. To see the article on home treatments for overactive bladder, click here.

Lifestyle changes and behavioural therapies

Advice about lifestyle changes and behavioural therapies are normally given by the GP prior to trying drug therapy. These include:

-

Absorbent Products.

Millions of adults use absorbent products to manage urinary leakage. While not a cure or even a treatment for the urge incontinence component of overactive bladder, use of shields, pads and undergarments (including adult diapers) are a popular defence against urinary leakage. Individuals can use these products without having to suffer the stigma of discussing their incontinence with relatives or health care providers.

-

Behavioural Modification.

Bladder training and scheduled voiding techniques are a non-invasive approach to managing OAB, often accompanied by the use of voiding diaries. These therapies help an individual to focus their awareness on the urinary tract, to develop bladder control and to increase the time between trips to the bathroom. Dietary changes are employed to reduce potential bladder irritants, which include limits on food and drinks containing caffeine and a reduction in drinks containing alcohol or sugar (including artificial sweeteners).

-

Pelvic Exercises and Biofeedback.

Pelvic floor exercises, such as Kegel exercises, are designed to strengthen the muscles surrounding the bladder and the urethra to help support the bladder. This increase in strength can decrease frequency and urgency. Biofeedback can be incorporated with pelvic floor exercises. These systems use a probe or electrode to help the user identify the appropriate pelvic floor muscles. When the correct muscles are contracted, the machine emits a signal and the user can focus exercise on these muscles. Because these techniques rely on the diligence and compliance of the individual, they have poor results. In addition, for overactive bladder symptoms, these techniques may not alter the underlying cause of the condition.

Drug therapy for overactive bladder

If lifestyle changes and behavioural therapies fail to improve the symptoms of OAB, the clinician will often prescribe anti-cholinergic or anti-muscarinic drugs. These are intended to strengthen the sphincter — the muscles supporting the bladder — thereby reducing the urgency, frequency and number of leaks. In patients who can tolerate these drugs, symptom improvement can be achieved in as many as 70% of patients. However, these drugs have many side-effects, which makes them poorly tolerated, especially by the elderly, and which affect compliance.

Common side effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, erythema, fatigue, urinary retention. Serious side effects, particularly in the elderly, include confusion and cognitive deficits. The use of drugs with reduced blood-brain barrier penetrance (such as darifenacin) may prevent cognitive side effects in these patients. Other central nervous system effects include dizziness, somnolence, insomnia, and sedation.

The American Urology Association (AUA) guidelines recommend exercising caution in prescribing anticholinergics to frail patients and NICE guidelines state that immediate release oxybutynin should not be offered to frail older women, defined as women with multiple medical comorbidities, functional impairments in activities of daily living, or any cognitive impairment.

Many woman are unable to tolerate drugs routinely prescribed for OAB, and more than 70% of patients discontinue these drugs within 1 year due to intolerability or ineffectiveness. Newer drugs, such as mirabegron, are more specific to receptors in the bladder and so reduce side-effects associated with the effect of the drug on other areas of the body. However, these newer drugs are more expensive than the older anti-muscarinics, so NICE advises they are prescribed only when the older drugs have been tried.

Invasive therapies for overactive therapy

If conservative methods or drug therapy are not successful, patients are referred for specialist review and consideration of invasive approaches. Invasive therapies are normally reserved for patients who have tried and failed to control their symptoms of OAB with conservative methods or drug therapy. The decision to try an invasive therapy will always follow urodynamic testing to confirm clinical suitability and a review by a multi-disciplinary team.

Invasive therapies included by NICE within its Clinical Guidelines are:

- Botulinum toxin

- Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS)

- Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)

- Augmentation cystoplasty

- Urinary diversion

Botulinum toxin (Botox)

The drug botulinum toxin is injected directly into the detrusor muscle of the bladder via cystoscopy. Botulinum toxin reduces the contractile activity (causing paralysis) of the bladder by selectively blocking the presynaptic release of acetylcholine from nerve endings.

Botulinum toxin has been shown to be effective in reducing urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence in around 70% of patients and significantly improves urodynamic parameters. It has been shown to be an effective treatment for patients who have not responded to more conservative measures; however, the effects of treatment with botulinum toxin start to wear off at six to nine months and repeat treatments are necessary.

The paralysing effect of the Botox on the bladder muscles is often such that more than one in five (20%) women has difficulty emptying her bladder for several months after treatment, necessitating the prolonged need for the woman to self-catheterise. All women undergoing Botox treatment must agree and be taught how to self-catheterise using disposable catheters to empty their bladder several times a day.

Dropout rate after two injections has been shown to be as high as 37%, with insufficient efficacy (13%) and temporary urinary retention (11%) being common reasons for discontinuation. Botox therapy also carries a significant risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) (5% over the initial 2 months) and an increase in urinary retention (33% post-void residual urine volume – PVR). This risk is higher in elderly, frail patients). Long-term treatment with Botox therapy has also been shown to have a high discontinuation rate.

Disadvantages of botulinum toxin for OAB

- One in five women has difficulty emptying her bladder for several months after treatment, necessitating self-catheterisation

- Very high drop-out rate after 2 injections

- Significant risk of urinary tract infection

- Significant risk of urinary retention

- Long-term treatment associated with high discontinuation rate

Botox treatment takes about 10-15 minutes and is carried out under local anaesthetic as a day case procedure. Generally, 200U of botulinum toxin A is used, although occasionally women will opt for a lower dose of 100U, understanding it to be less effective, but with a lower risk of requiring catheterisation.

Criteria for use of botulinum toxin for the management of OAB:

- Patients have been managed and treated according to the relevant NICE clinical guideline 171

- Patients have been supported with behavioural and lifestyle advice and a trial of at least two medications, but have not had a positive response to these interventions

- A multidisciplinary team has considered botulinum toxin to be the most appropriate treatment

- Patients are willing and able to self-catheterise

- Informed consent has been obtained

- Symptoms are refractory to lifestyle modification (caffeine reduction, modification of fluid intake, weight loss if BMI >30)

- Symptoms are refractory to behavioural interventions: a minimum of 6 weeks of bladder retraining or 3 months of pelvic floor muscle training (in mixed urinary incontinence only, where there is some stress incontinence as well as OAB)

- Symptoms are refractory to 4 weeks of anticholinergic medication to a maximal tolerated dose (a number of drugs may be tried in accordance with NICE CG171) [or mirabegron, in people for whom anticholinergic drugs are contraindicated or clinically ineffective, or have unacceptable side effects (NICE TA290)]

- The woman has been reviewed by a urinary incontinence MDT and a diagnosis of detrusor overactivity has been confirmed by urodynamic assessment

- The woman is willing and able to perform clean intermittent catheterisation

- The treatment with botulinum toxin is initiated by a Consultant Urologist or Gynaecologist

Sacral nerve stimulation (neuromodulation)

Normal urinary control is dependent upon neural pathways that are functioning properly and coordination between the central and peripheral nervous systems, the nerve pathways, bladder and sphincter. Unwanted, uncoordinated or disrupted signals along these pathways can lead to symptoms of overactive bladder. Therapy using neuromodulation incorporates electrical stimulation to target specific neural tissue and interrupt the pathways transmitting unwanted signals. To alter bladder function, the stimulation must be delivered to the sacral nerve plexus, the neural tissue affecting bladder activity. Currently neuromodulation options for OAB include percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS; the subject of this business case) and the more invasive sacral nerve stimulation.

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) therapy involves the use of electrical pulses to stimulate the sacral nerves located in the lower back. Electrodes are placed next to a sacral nerve in the patient’s back. The electrodes are subsequently attached to a battery-operated pulse generator. Prior to ‘permanent’ implantation, responsiveness is tested using a test period of treatment using an external stimulator. This involves the use of a temporary wire electrode, which is later removed, or using a tined electrode, which can be left in permanently. A patient is suitable for permanent implant if they report a significant improvement in symptoms (recorded in a bladder diary).

In a carefully selected and small group of patients, SNS provides sustainable symptom relief. Studies have shown that 80–90 % of patients who received a permanent implant experienced a greater than 50% improvement in their objective symptoms, with a significant decrease in incontinent episodes per day. Benefits of SNS were reported to persist at follow-up three to five years after implantation.

Adverse events include pain (24%), lead-related complications (16%), wound problems (7%), modifications of bowel function or adverse bowel function (6%), infection (5%), problems related to the implanted pulse generator (5%).

SNS requires an operation under general anaesthetic and recovery time of one day. Over time, the electrodes can move in the body, and studies have shown that 33% need further surgery to reposition them. The battery usually needs to be replaced every 3 to 5 years, but occasionally sooner. This procedure requires two stages of treatment; the trial stage (to evaluate whether the treatment will be effective) for all women. Under half of these are expected to progress to receiving the second stage. SNS has been shown to be effective in treating OAB, but its use may be limited due to its high cost(<£9000), surgical implantation and potential requirement for surgical revision. The increased use of other therapies (Botox and PTNS) in women with OAB who are resistant to drug treatment is expected to decrease the number of women being treated with sacral nerve stimulation.

Sacral Nerve Stimulation (SNS) lies outside the UK NHS Payment by Results tariff and requests are considered on an individual patient basis by NHS England.

Criteria for sacral nerve stimulation for the management of OAB

SNS is a specialised service commissioned by NHS England for adult patients with urinary urgency incontinence, urinary urgency-frequency syndrome or double incontinence (urinary and faecal) who meet the following criteria:

- A confirmed diagnosis defined by a quality controlled conventional urodynamic assessment or ambulatory Urodynamics when indicated. If the urodynamic diagnosis is inconclusive, a decision for further management including SNS must be made at an incontinence MDT.

- Symptoms which are refractory to behavioural and lifestyle modification, pelvic floor exercises and pharmacological therapy; at least two anticholinergics followed by a beta-3 agonist unless such treatments are contraindicated.

- Female patients who have been offered intra-vaginal oestrogens for the treatment of symptoms of OAB in postmenopausal women with symptoms of vaginal atrophy where clinically appropriate.

- Patients not suitable for treatment with botulinum toxin bladder injections, including any of the following:

- The patient is unable to perform clean intermittent catheterization

- There is a medical contraindication to botulinum toxin treatment

- Botulinum toxin bladder injections have not had a therapeutically useful effect

- An incontinence MDT has recommended that SNS is a more appropriate treatment.

- Referred to a specialist surgeon at a centre experienced in providing SNS and after review by the incontinence MDT.

- Patients who have been counselled about

- the surgical and non-surgical options appropriate for their individual circumstances,

- the benefits and limitations of each option, with particular attention to long- term results,

- realistic expectations of the effectiveness of SNS including the risk of failure, the long-term commitment, the risk of complications requiring reoperation and device removal and possible adverse effects.

- Does not have a physical or mental disability, which prevents a safe level of cooperation with the technical demands of the procedure. (Formal evaluation should be performed if necessary).

- Does not have a known condition likely to necessitate future MRI scanning (as MRI contraindicated after SNS treatment, except MRI of head)

Augmentation Cystoplasty

In rare cases, a procedure known as augmentation cystoplasty may be recommended to treat OAB. This is reserved as a last option after other treatments have proven unsuccessful. Bladder augmentation increases the capacity of a small, hyperactive or non-resilient bladder by adding bowel segments (ileum, cecum or ileocecum) to enlarge the bladder. The smooth detrusor muscle that contracts the bladder is cut out of the dome of the bladder, leaving the mucous membrane intact to reduce muscle contraction and improve bladder function. After the procedure, patients may not be able to pass urine normally and may need to use a catheter, which can lead to recurrent urinary tract infections.

Urinary diversion

For a rare number of patients with refractory OAB, creation of an ileal conduit urinary diversion is an option, particularly for those who might be deemed unsuitable for augmentation cystoplasty. Complications include the risk of recurrent UTI and upper tract dilatation, and the possibility of renal function deterioration in the longer term.

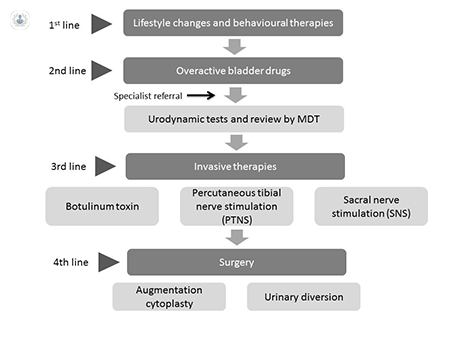

Guidelines on overactive bladder

The following summarises the most recent guidelines for treating women with OAB. All of the guidelines recommend a trial of conservative methods, followed by drug therapy only if conservative methods fail to adequately improve symptoms. Referral to secondary care is recommended if drug treatment is not successful, and the patient would like to consider further treatment options. If urodynamic investigation determines that detrusor over activity is present and responsible for the patient’s OAB symptoms, then invasive therapy should be offered after review by a multidisciplinary team. The following describes the different recommendations for invasive therapy contained within the NICE guidelines, European guidelines and US guidelines.

In summary, this article offers a simple pathway process to follow for the management of OAB. It can be seen that there are many options available for this common condition and patients can be reassured that their symptoms can be controlled using simple measures initially, escalating to more complex procedures if required.