My child has kidney reflux.. how can it be treated?

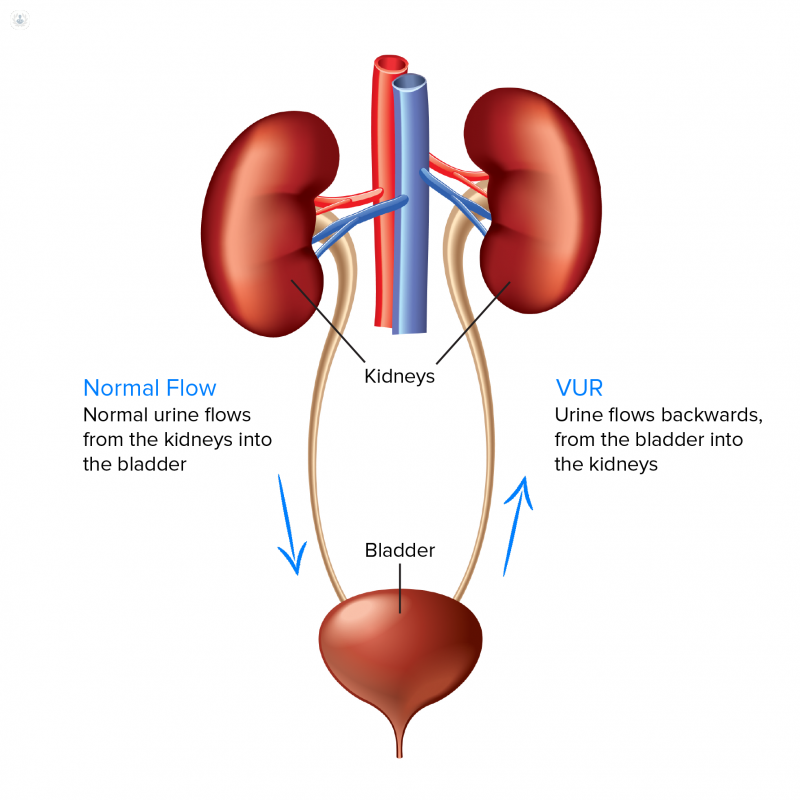

Written by:Kidney reflux occurs in 1-2% of children, although not all cases require treatment. It is a condition in which some of their urine flows in the wrong direction after entering the bladder and goes into one or both of the ureters, and sometimes the kidneys.

It is one of the more common reasons for a child to be referred to a paediatric urologist and can put your child at a higher risk of developing a urinary tract infection.

In this article, Miss Marie-Klaire Farrugia, a leading paediatric urologist, discusses the principal causes of kidney reflux, how it is diagnosed and offers us an overview of the various treatments available to relieve your child of this problem.

What is kidney reflux and are there different types?

The technical term for kidney reflux is vesico-ureteric or vesico-ureteral reflux (VUR). There are two types of VUR:

- Primary — whereby the baby is born with the condition.

- Secondary – whereby VUR develops as a result of poor bladder function in other conditions, such as posterior urethral valves or in patients with spinal abnormalities.

What are the causes of kidney reflux?

Primary VUR may be “physiological” – i.e. usually self-limiting and not generally associated with kidney problems or infections. This is because the “valve” between the ureter and the bladder takes up to two years to function properly, and once it does, the reflux stops. This scenario is usually found with completely normal kidneys and bladder.

More serious VUR can be associated with scarring or poor function in the affected kidney. This scenario could lead to recurrent urine infections with fever, repeated courses of antibiotics, and further damage to the kidney if the infections are not treated promptly.

How is it diagnosed?

VUR may be suspected on antenatal ultrasound scan (in pregnancy) when the fetus is seen to have a hydroureteronephrosis (swollen kidney and ureter) or megaureter (a bigger ureter than normal); or after the child presents with severe urine infection with a high fever.

The test commonly used to diagnose VUR is called a micturating cystourethrogram (MCUG), whereby a thin soft catheter is inserted via the urethra to allow contrast to be inserted into the bladder. An x-ray will then show contrast flowing up into the kidney if VUR is present.

If “high-grade” or severe VUR is seen, the specialist may recommend a DMSA scan which specifically looks at kidney function and any scarring.

How is kidney reflux treated?

Mild, physiological VUR often requires no treatment. However, in cases of more severe reflux, the child is started on a small dose of antibiotics every evening - usually Trimethoprim at a quarter of its normal dose. This prevents the child from getting urine infections until the VUR resolves. It is more likely to resolve if the kidneys are normal, and if the child drinks well, pees regularly and is not constipated. The specialist will advise how long the child needs to stay on prophylaxis for, which usually at least for the first year of life, but can sometimes be longer.

In boys with kidney reflux, a circumcision may be recommended as it helps reduce the risk of urine infection.

Some babies and children will, unfortunately, suffer a febrile urine infection while on antibiotic prophylaxis. This is a sign that surgical intervention is required.

What type of surgery is offered?

The first-line surgical option is a procedure called a STING or sub-ureteric injection of a substance, commonly Deflux. This is performed under a quick general anaesthetic through the urethra and into the bladder, so no cuts or open surgery are required. It is commonly performed as a day case and has a high success rate.

An alternative option is ureteric reimplantation – or re-plumbing of the ureter into the bladder to stop the reflux. This is a more complex procedure, performed by key-hole surgery or by a cut in the lower pelvis. It requires a hospital stay of 2-5 days depending on the technique used.

What happens if kidney reflux is left untreated?

Benign VUR may improve without treatment, and VUR which is causing repeated infections is not likely to improve and may damage the kidneys further. Recurrent courses of antibiotics may result in resistant bugs which become more difficult to treat.

What aftercare is needed?

A STING or Deflux injection is an out-patient procedure and recovery is quick. I normally recommend an ultrasound scan 4-6 weeks later, and if the scan is normal, antibiotic treatment can be stopped.

Miss Marie-Klaire Farrugia is a consultant paediatric urologist based in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and the BUPA Cromwell hospital in central London. To book an appointment or e-Consultation with her, visit her Top Doctors profile and check her availability.