“One day I’d love to say ‘I used to have HIV’.” An anonymous quote on a motivational poster, but it’s one that resonates. It has been over three decades since HIV/AIDS was first observed and identified, and there are still around 36.9 million people around the world living with the disease. 30 years, and no cure.

Of course, things have improved. Thanks to modern antiretroviral drugs, AIDS is not the prolific killer it once was, and many patients live full, healthy lives as long as they stick to their meds. But suppressing the virus is not the same thing as curing it and many in the AIDS community remain painfully aware of their condition.

Then came 2007. The world’s first case of HIV remission was reported. The so-called “Berlin patient” offered hope for the impossible. People around the world dared to wonder: “could this be the beginning of the end for the AIDS epidemic?” Alas, the noughties gave way to the 10s and as we approach the end of another decade, the success still had not been replicated. Until now.

Suddenly, HIV is back in the news, with another case of an apparent “cure”. The individual, dubbed the “London patient” has been off HIV treatment for a year and a half, with no signs of the virus re-emerging. What does this mean for the fight against AIDS?

The Berlin patient

The first person to be cured of HIV was Timothy Ray Brown, initially dubbed the “Berlin patient” for the sake of anonymity until he decided to announce his identity in 2010. The American was living in Germany in 1995 when he was diagnosed with HIV. Initially, his disease was kept under control with antiretroviral therapy, but a decade later, he was diagnosed with a second, even deadlier condition: acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

Brown was initially treated with several rounds of chemotherapy, which sent the leukaemia into remission, but when it rebounded in 2007, he was given a potentially risky stem cell transplant. While this was primarily a treatment for the cancer, German doctor Gero Hütter had the idea of finding a donor with a particular rare gene mutation that can block HIV from entering a certain type of white blood cell. After a second stem cell transplant in early 2008 and a nasty battle with graft-versus-host disease, Brown came out the other side with no signs of HIV in his blood.

The London patient

For over a decade, Brown has been a one-of-a-kind success story. Doctors and scientists researched the methods used to cure him, but many wondered if his recovery was simply an anomaly in the ongoing war against AIDS; that the success couldn’t be replicated – or shouldn’t, given his near-death experience with graft-versus-host disease. However, this year, this has all changed.

Much like Brown, the London patient had been treated for cancer, and after chemotherapy and radiotherapy had failed, a bone marrow transplant was recommended. The doctor in charge – Ravindra Gupta, of the University of Cambridge – chose a donor with the same rare mutation in the CCR5 gene. To prepare for the transplant, the patient was given immunosuppressive drugs, but of a less aggressive nature than those given to Brown.

The London patient remains anonymous, but, like the Berlin patient before him, his story has been presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) and has attracted the attention of the media.

Researchers warn to be cautious – it is still early to say whether the patient’s HIV has definitely been cured, but after 18 months without antiretroviral therapy, there is still no sign of the virus.

The science behind the “cure”

The procedures used to treat both the Berlin and London patients were remarkably similar. Both had undergone cancer treatment and received a transplant of stem cells from the bone marrow of donors.

So what are stem cells? Stem cells are basically undifferentiated, “blank” cells that have the potential to become any kind of cell in the body. We all have stem cells in our bone marrow, which are deployed to various parts of the body when needed. They develop into the kind of cell that is needed in each location, whether that is a muscle cell, a blood cell, or a brain cell.

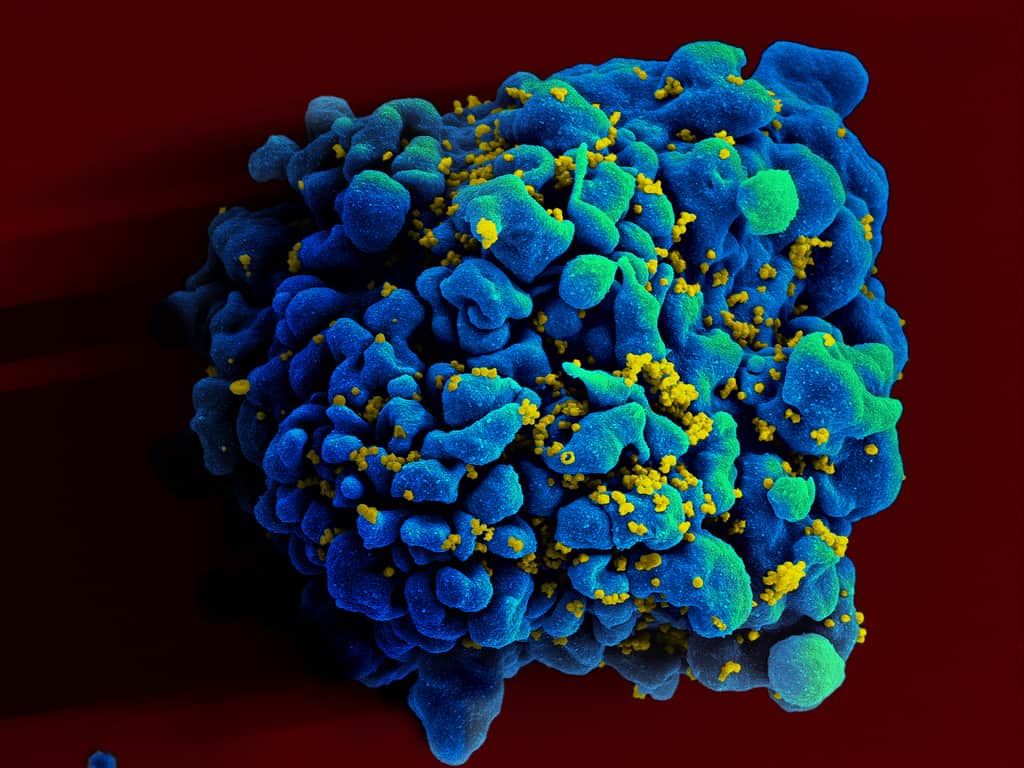

In this case, the transplanted stem cells become white blood cells – proponents of the immune system that combat disease. The body’s own white blood cells have been invaded by HIV, weakening the immune system. This leads to AIDS, in which the patient is in danger of becoming seriously ill or even dying from opportunistic illnesses that a healthy person wouldn’t be troubled by.

However, it is believed that stem cells alone are not enough to put an end to HIV. After all, logically, the virus could go on to invade the new white blood cells too. Couldn’t it?

This is where CCR5 comes in. CCR5 is a protein on the surface of white blood cells, which functions as a receptor (it allows the cells to pick up biological signals). HIV uses this protein to invade its target cells – in other words, CCR5 hands HIV the keys to the kingdom, allowing it to wreak havoc on the body’s immune cells. The solution exploited by doctors treating the Berlin and London patients was to change the locks.

Certain people are born with a rare genetic mutation in the CCR5 gene. This mutation (known as CCR5-Δ32 or CCR5 Delta 32) offers resistance to HIV-1. People with two copies of this gene have no functioning CCR5 receptors on the surface of their white blood cells and resist infections with HIV-1. Those with only one copy have less than half the CCR5 receptors as the average person and exhibit reduced viral loads when infected with HIV, along with a much slower progression to AIDS.

When choosing a stem cell donor for Brown and the London patient, their doctors sought out individuals with two copies of the CCR5-Δ32. When the stem cells differentiate into white blood cells, these genes come into play, barring the HIV entry and allowing the immune system to continue to combat infections.

The London patient is one of 38 HIV patients who have been given bone marrow transplants currently being monitored by a European consortium called IciStem. This group has compiled a list of 22,000 donors with the mutant CCR5 gene and has used transplants from these in all but six of the patients. Amazingly, the study has already yielded a possible third success story. The patient, dubbed the “Dusseldorf patient” has only been off antiretroviral medication for a few months, so it is too early to be sure that the virus is gone. For now, however, it appears that his condition is improving.

The future of HIV treatment?

With two success stories and possibly a third, you might think that the battle against AIDS could soon be won. However, researchers urge caution with regarding this breakthrough as a viable cure for several reasons:

- Stem cell transplants can be risky – as evidenced by the fact Timothy Brown nearly died of graft-versus-host disease. They are generally reserved for patients whose odds of survival without the transplant are low to non-existent.

- Finding donors with two copies of the CCR5-Δ32 is no mean feat. The mutation is more common among people of Northern European descent, but even in Europe only 1% of the population have both copies; in other populations it is even rarer.

- Not all variants of HIV use the CCR gene to invade cells. While CCR5-Δ32 may offer resistance to most strains of HIV, it will not necessarily impede all strains.

- While antiretroviral therapy makes it possible to a live a full and normal life while managing the disease, it is simply not worth subjecting most patients to a turbulent, risky, and expensive treatment. In the words of Professor Graham Cooke of the NIHR and Imperial College London, “At the moment the procedure still carries too much risk to be used in patients who are otherwise well.”

In the end, the consensus is that stem cell transplants are not a practical option to treat the millions of HIV patients across the globe. That isn’t to say, however, that the stories of the London patient and Berlin patient aren’t significant. By understanding more about how it is possible to block HIV and why stem cell treatments work in some patients and not others, we will continue to get closer and closer to a world where people can look back and say “I used to have HIV”.

Sources:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/04/health/aids-cure-london-patient.html

https://stemcells.nih.gov/info/basics/1.htm

https://www.bbc.com/news/health-47421855

Join the discussion