Targeted therapy

Dr Matthew Winter - Medical oncology

Created on: 11-14-2022

Updated on: 01-16-2024

Edited by: Carlota Pano

What is targeted therapy?

Targeted therapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses drugs to target specific features within or on the surface of cancer cells that help the cells grow, divide, and spread. It is the basis of precision medicine.

How does targeted therapy work?

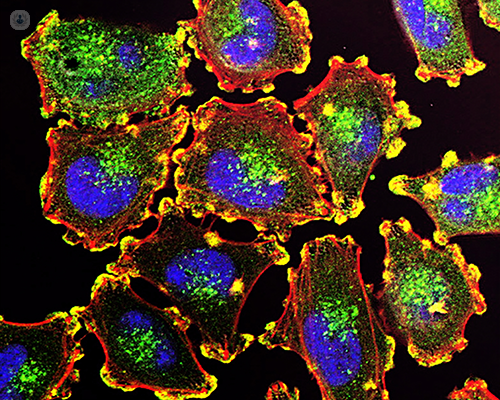

The human body is made up trillions of cells, which carry out specific functions. Each cell has a nucleus, which contains chromosomes that are made of DNA, a complex molecule that contains genes. Each gene carries the genetic information needed for cells to make proteins, which perform different functions.

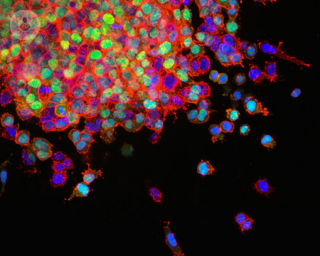

Cancer begins when certain genes in a cell change (called mutation or alteration) and become abnormal. Proteins also change, as a result. When this occurs, cells start to behave differently – for example, multiplying faster and living longer than they should. In some cases, these gene changes can also create features (known as targets) within or on the surface of the cancer cells that help the cells to grow. Targeted therapy drugs identify and attack these targets.

Each targeted therapy drug is designed to act on a particular target. This can treat cancer in different ways, including:

- Interrupting signals that tell cancer cells to grow

- Destroying cancer cells

- Changing proteins within cancer cells so that the cancer cells die

- Helping the immune system to destroy cancer cells

- Delivering specific substances to cancer cells to them

- Stopping the cancer from growing blood vessels

Targeted therapy drugs will only be given if cancer cells have a target. For this reason, not even patients with the same cancer type are guaranteed to be suitable candidates for targeted therapy.

What are examples of targeted therapy?

There are different types of targeted therapy drugs. These are grouped together depending on how they work. The two main groups of targeted therapy drugs are small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies.

- Small molecule inhibitors

Small molecule inhibitors are drugs that are small enough to get inside cancer cells easily. For this reason, they are used to block certain proteins inside cancer cells that tell the cancer cells to grow and spread.

Types of small molecule inhibitors include:

- TKIs (which block tyrosine kinases proteins)

- mTOR inhibitors (which block mammalian target of rapamycin proteins)

- PARP inhibitors (which block poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase proteins)

- CDK inhibitors (which block cyclin-dependent kinase proteins)

- Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are synthetic (manufactured) proteins produced in a lab that act like human antibodies (proteins produced by the immune system to fight infections).

These synthetic antibodies are designed to lock (attach) onto specific receptors found on the surface of cancer cells and in the environment surrounding the cells. These receptors help cancer cells send and receive signals. By locking onto cancer cells’ receptors, monoclonal antibodies can control cancer cells, for example, by blocking signals that tell the cells to grow.

In some cases, monoclonal antibodies may be designed to carry and deliver radiation directly to cancer cells. In others, monoclonal antibodies may work to help the immune system recognise and attack cancer cells more easily. For this reason, monoclonal antibodies may be considered immunotherapy as well. However, this depends on the type of monoclonal antibody.

Types of monoclonal antibodies include:

- angiogenesis inhibitors (which block cancer cells from growing new blood vessels that nourish and provide cells with oxygen)

- HER2-targeted agents (which block or limit the HER2 protein that causes cancer cells to grow uncontrollably)

- anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (which block the CD20 protein)

Other types of targeted therapy drugs include apoptosis inducers (which induce the death of cancer cells) and other immunotherapies.

When is targeted therapy recommended? Who is a suitable candidate?

Targeted therapy is not suitable for all types of cancers.

For some types of cancer, an oncology specialist will test a patient’s sample of cancer cells to see if the cells contain a particular target that is helping the cancer grow. This procedure is called a biopsy and it is done to find out whether targeted therapy is likely to work.

Patients will receive different cancer treatments (such as surgery, radiotherapy or chemotherapy) based on their test results. This will happen even among patients with the same cancer type.

Currently, targeted therapy is suitable for melanoma and some types of leukaemia, such as chronic myelogenous leukaemia.

How is targeted therapy given?

Targeted therapy drugs are available in different formats:

- As tablets or capsules that can be swallowed

- As an IV infusion into a vein, either into a port or through a drip in the arm

- As an injection underneath the skin

If targeted therapy is found to be suitable, treatment may be given on its own or in combination with other cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy. Some targeted therapy drugs are given in periodic cycles with breaks, while others are taken every day without rests in between.

The duration of treatment will depend on the aim of treatment, the response of the cancer, and the side effects experienced by the patient. Commonly, targeted therapy drugs will need to be taken long term, daily for several months or years. Despite this, most patients are able to continue with their normal activities and have a good quality of life.

What are the possible side effects of targeted therapy?

Targeted therapy can still cause severe side effects. These can begin within days of starting treatment but, most commonly, will occur weeks or months later.

Some patients may not have side effects at all, while others may have several. The exact side effects that patients may experience will depend on the type of targeted therapy drug received and the body’s response to the drug.

The most common side effects of targeted therapy include:

- Skin problems, including acneiform rashes, redness, swelling, flakiness, dry skin, and hand-foot syndrome

- Fever

- Joint aches

- Nausea

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Itching eyes with/without blurry vision

- Diarrhoea

- Bleeding

- Bruising

- High blood pressure

In rare occasions, some targeted therapy drugs may affect how the heart, lungs, thyroid, or liver function. If left untreated, some of these side effects may lead to severe heart and lung health issues.

Some targeted therapy drugs can increase the likelihood of getting an infection.

How successful is targeted therapy?

Blood tests and different types of scans will be regularly ordered to see whether the cancer is responding to targeted therapy.

A positive response is cancer that shrinks or even, completely disappears. In some cases, however, the cancer may remain stable (meaning that it doesn’t grow in size), but at the same time, does not shrink or disappear. Patients with stable cancers need close monitoring, but will be able to have a good quality of life.

What is the difference between targeted therapy and chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy drugs affect all cells in the body that multiply quickly. This means that the drugs can kill cancer cells, but also damage other cells, including healthy cells. The effect of chemotherapy drugs on healthy cells can cause a wide range of side effects, for example, nausea, hair loss, and mouth ulcers.

Targeted therapy drugs work in a more focused way. They also kill cancer cells, but they limit the damage to healthy cells, mostly leaving healthy cells alone. As a result, targeted therapy often has fewer side effects than chemotherapy.